How does a Hen make an Egg?

How a hen makes an egg is a remarkable journey showing nature's complexity and efficiency, enabling hens to lay eggs almost daily.

So, let me describe how we can travel from egg cell to egg box - in just a day!

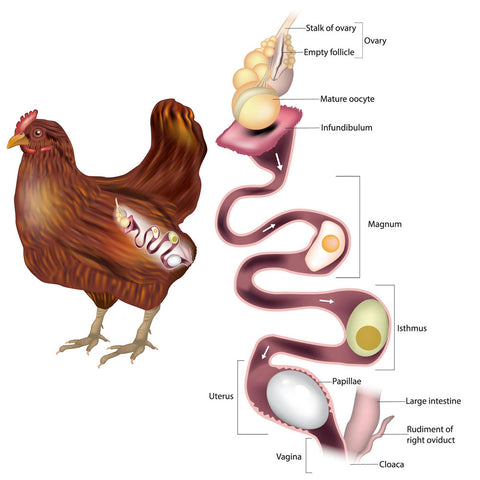

The physiology of making an egg involves several biological steps. The entire process from ovulation to laying a shelled egg takes about 24 hours.

It starts with the ovary of course (no input from a male is needed for egg formation to begin).

Hens have two ovaries, but usually only the left one is functional. This ovary contains thousands of ova (egg cells) that can potentially develop into eggs.

When a hen reaches maturity which, depending on breed, can be from 18 to 22 weeks old, hormonal changes trigger the development of an ovum into a yolk.

This yolk is released into the oviduct where the egg will be formed. The oviduct is a long winding tube made up of several sections including the magnum (egg formation), the isthmus (shell membrane added), and the uterus or shell gland where the shell hardens.

As the yolk moves through the oviduct, it is encased in layers of albumen (egg white), which provides protection and nutrients.

Further down the oviduct, membranes form around the albumen and yolk. The egg then reaches the shell gland, where the shell is formed over a period of about 20 hours. The shell is primarily made of a crystalline form of calcium carbonate and is deposited layer by layer around the yolk and albumen.

Plenty of calcium is essential for a hen to produce a nice thick, smooth eggshell. Providing sources of calcium and vitamin D3 in their diet is essential.

Giving hens oystershell and a vitamin tonic will help this, especially during winter months when daylight is limited. Otherwise, if needed, hens could ‘rob’ their skeleton of calcium to ensure robust eggshells, which would be detrimental to her long-term health. See more on calcium and vitamin D in: Solving Problems with Egg Shells.

The shell is soft as the egg travels through the oviduct. As it nears the end of its journey it hardens to make sure it is strong enough to withstand the outside environment.

As the egg leaves the hen’s body through the cloaca, it receives a protective coating, or bloom, to seal the pores against contamination. So, you will find a lovely clean egg laid in the nest.

In female birds, the cloaca is a multi-purpose opening for the expulsion of bodily waste, and it also serves as the exit for laying eggs. Don’t worry though, the hen’s body cleverly expands the oviduct to ‘close’ the waste tube and allow a clean egg to be laid.

After laying an egg, the hen usually has a short rest period before the cycle starts again. Hens, unlike wild birds, are domesticated (farm) birds, bred for egg laying and meat production.

Wild birds, and other non-domesticated birds, however, lay their eggs infrequently. Evolution has tailored them to lay eggs for breeding and in seasons when the environment favours survival of their young.

For more on which breeds of chickens lay the most eggs, what colour shells are produced, visit How many Eggs can a Hen Lay, and for a potted history of most popular breeds, see our Chicken Breeds Info page.

The Anatomy of an Egg

The anatomy of an egg is quite complex, but it is a lovely little miracle of nature containing every nutrient for life (except Vitamin C). It consists of several parts, each with a specific purpose, and is created in a hen’s body within 24 hours!

As described above, it all starts with an egg cell, then layer upon layer an egg is formed. The hen then dutifully leaves the egg in her nest for us to collect and enjoy.

To break it down into all the layers in more detail, let’s start at the beginning, and work outwards - like the hen does.

The egg cell, the Germinal Disc, is seen as small, white spot on the surface of the yolk where the hen’s genetic material is located.

The hen's ovary releases the ovum to begin its journey, first creating the yolk. If the egg is fertilised, you will see this as a tiny pink spot on the yolk which is where the embryo would develop. Sometimes you may see larger red specks on the yolk, but this is simply that a blood vessel has broken during formation of the egg.

The Yolk is the nutritious recognisable yellow part of the egg, rich in fats, proteins, vitamins, and minerals. It contains all of the fat and cholesterol (and calories) of the egg - as well as calcium, manganese, protein, folic acid, iron, thiamine, selenium, zinc, vitamins A, B D, E, and K - packed full of nutrition!

It would be the main food source for the developing embryo, should the egg be fertilised. The colour of the yolk can vary from pale yellow to rich orange based on the hen's diet; for instance, free-ranging birds with access to sunshine, grass and grains will lay eggs with brighter yolks whereas hens raised indoors may produce paler yolks (unless their feed is supplemented with yolk colourants).

Next comes the Vitelline Membrane, a very thin, see-through layer that wraps around the yolk of an egg. It keeps the yolk in place and separates it from the thick part of the egg white (thick albumen). Think of it as the final layer of protection for the yolk. It is what makes the yolk of a fresh egg sit up in the egg white but, as the egg ages this membrane weakens making it more likely the yolk will break in the pan.

Chalazae are spiral bands of protein that act like springs on either side of the yolk. They are two rope-like structures, made of twisted strands of egg white (albumen), anchoring the yolk in the centre of the egg white. They absorb shock to prevent damage to the yolk.

Surrounding the yolk is the Albumen, usually called the Egg White. It consists of four layers of protein-rich fluids that vary in consistency.

The Albumen may only contain 17 calories, because it has no fat or cholesterol, but it does have riboflavin (which gives it that yellow hue), potassium, niacin, and sodium.

The Thicker Albumen, closest to the yolk, provides cushioning and protection to the yolk. It contains water and proteins essential for the embryo's growth if an egg were fertilised.

The Thin Albumen is the outer egg white visible as the outer, flattest, edge of a fried egg, for example. As the egg ages, the Albumen becomes thinner, causing older eggs to spread out in the pan far more than a fresh egg.

At the larger end of the egg, between the inner and outer shell membranes, is the Air Cell.

This space develops as the egg cools and contracts after it's laid, and gradually expands as the egg ages.

A good test of the age of an egg is whether it floats in a pan of water (thereby older and containing a large air cell), or whether it sits at the bottom of the pan, or somewhere in between.

Beneath the shell are the inner and outer Shell Membranes. These membranes separate the egg white from the shell and provide protection against bacteria as well as help maintain the egg's internal structure. The membranes shrink and separate as the egg cools, allowing air to seep in, which expands the Air Cell. This is why it is better to boil eggs from older eggs because the separated membranes make it easier to peel off the egg shells.

The Shell is, of course, the outermost layer of the egg, the first line of defence against microbial invasion and physical damage. Approx. 10% of the weight of an egg is shell.

It is made primarily of calcium carbonate - hence why hens need plenty of soluble calcium in their diet in the form of Oystershell. Without sufficient calcium, they will take it from their bones, or lay thin-shelled, misshapen eggs.

The Shell is porous, allowing for gas exchange, and typically contains around 7,000 to 17,000 tiny pores which allow gases to pass through the shell, regulating internal air pressure within the egg, and providing air for a developing embryo.

The Shell Colour Pigment depends on the breed genetics of chicken and is usually applied to the outside of the shell.

All eggshells are formed as white with the pigment being either brown or blue. The blue pigment can sometimes seep into the inside of the shell turning it blue whereas the brown pigment tends to leave the inside white.

Some breeds (like Cream Legbars) can have both pigments and their eggs may look sometimes green, or sometimes blue (specific to an individual hen though). Arucanas lay blue eggs, whereas a Marans lays dark brown eggs with white insides.

Finally, the Cuticle. This is the ‘Bloom’ that coats the outside of the eggshell. It is an almost invisible natural coating that helps to seal those thousands of pores and keep out air and bacteria. Washing an egg removes this bloom, which in turn allows the egg to age more quickly. However, it would flake off anyway as the egg ages.

All these complex components work together seamlessly to create a beautiful egg which will protect and nourish a potential embryo or, as most eggs are consumed in the human diet, to provide incredible nutritional value. A remarkable natural marvel!

However, sometimes things can go awry and an egg is laid with a deformed shell, a soft shell, or no shell at all - check our our blog page for About Problem Egg Shells.

"The hen's egg, a marvel of nature's design, is a humble yet profound testament to life's intricate mystery. Encased within its unassuming shell lies the blueprint of existence, a silent symphony of creation, where the simplest of forms harbours the promise of a new beginning. It stands as a delicate reminder that within the ordinary, the extraordinary finds its birth." ~ Anon

How a Hen makes an Egg ©Flyte so Fancy 2024. Author: Anne Weymouth (Director, Flyte so Fancy Ltd). Reproduction of part or all of this text and images is only possible with the express permission of Flyte so Fancy Ltd.